FIRST D-DAY PHOTOS PART 2

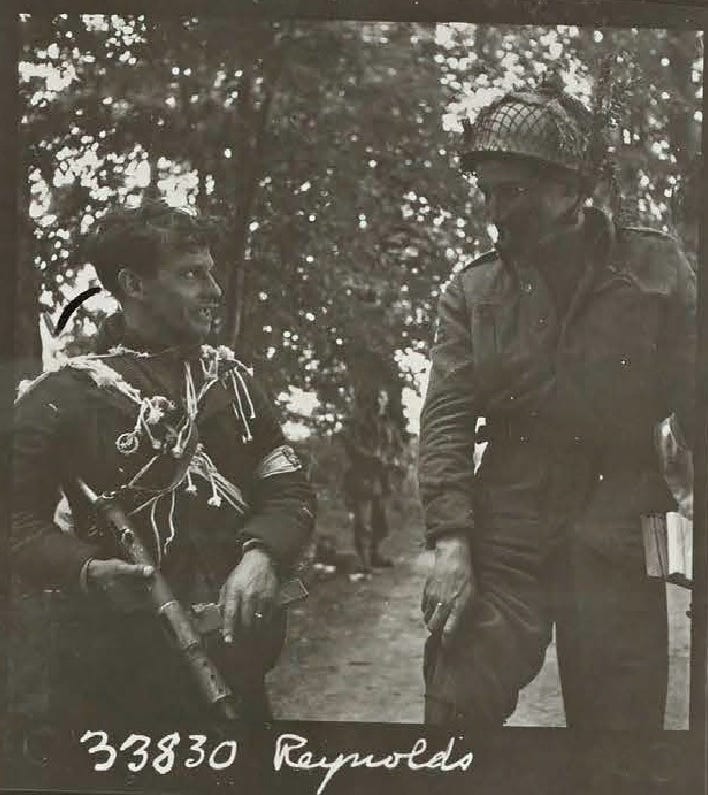

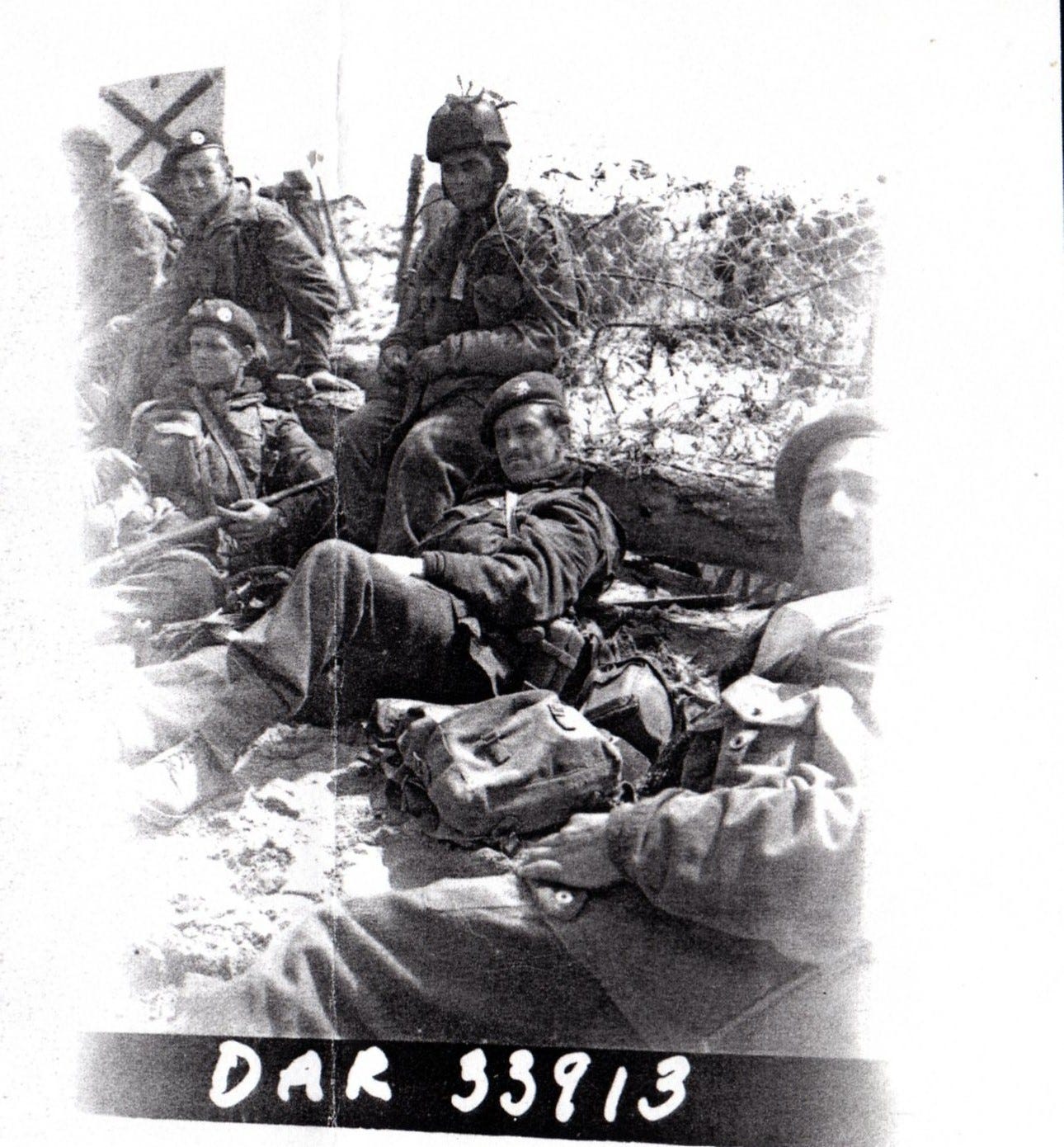

“FIRST INVASION PIX” Canadian paratrooper Sgt. Dave Reynolds The first photographer to land on D-Day

Sgt. David Alexander Reynolds was the first Allied cameraman to land in Normandy on D-Day recording the first few days of the 6th Airborne Division in battle, in particular his unit, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

Few photographs exist of the 6th Airborne Division in Normandy with few army photographers to record their exploits and because of security cameras were scarce amongst servicemen in case of capture. There are only eleven photographs available in the Canadian archives taken by Reynolds in the area of Le Mesnil and Sword Beach showing German prisoners of war, a French partisan, wounded airborne troops and a group of glider pilots on Sword beach.

Before Reynolds enlisted into the Royal Canadian Signal Corps he was a Radio announcer at CHML [Hamilton Maple Leaf] Radio station said to have worked with Charlie Chaplin. He was sent oversees to England with the 1st Canadian Infantry Division where he transferred to Canadian Army Film and Photographic Unit, Canadian Public Relations Group.

The Unit was created in October 1941 to document the Canadian Army in training and battle. Made up of skilled cameramen in film and photography to record the war and the men who fought it, it was attached to units armed with their roll of film taking photos of soldiers at rest and in battle, some posed and in battle, recreating the war for the readers back home.

After a six week course in cine and still cameras in June 1943 Reynolds became an accomplished cameraman and along with another cameraman, Bonter, both volunteered for parachute training becoming part of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion which came under the aegis of 6th Airborne Division. He was filmed receiving his jump wings at Ringway Parachute Training School on the 18th October 1943.

Reynolds would be retracing his father’s expedition to France who had served and died in France during the Great War falling at Passchendaele in 1916. Reynolds recalled “We stayed in transit areas of England four or five days before D-Day and although tension was high, morale was very high too. When the big event was postponed spirits sagged very low but climbed again when the go ahead signal came Monday [5th June 1944]. Paratroops call it “panic” – you know hands shake and knees knock. We wrote last letters and were allowed to say we were going to France that night. We went around the [transit] camp saying goodbye to each other and making dates to see each other over there later on. Paris seemed a favourite place to arrange for future dates. Then out to the airfield and aircraft.”

Reynolds was armed with a Mk V Sten gun but also his tools of the trade 16mm Victor cine and Rolleiflex still cameras, he put his 35mm Eyemo cine camera and tripod in a glider which should arrive after he landed. At Down Ampney airfield he emplaned with the rest of the Canadian Parachute Battalion in Dakotas with Major Holborn’s stick made up of fifteen troops. As the aircraft taxied for take-off the Dakota would not turnover and was unserviceable due to a blocked cylinder forcing pilot F/L. Metcalfe, his crew and the stick to change to a spare Dakota.

Reynolds continues “We took off four minutes late [23.29 hrs] with big 75 pound packs strapped to our legs and were supposed to be in air an hour and fifty minutes. Going across the channel everybody was cheerful but there was no singing. When the action stations order came it was supposed to mean 15 minutes to go but we had been more than ready for an hour.”

Most of the parachute sticks dropped at around 01.00 hrs onto Drop Zones marked out by pathfinders half an hour before. As the aircraft approached the French coast Lt. Holborn checked the stick’s static lines; just as they were about to hook up heavy flack hit the aircraft

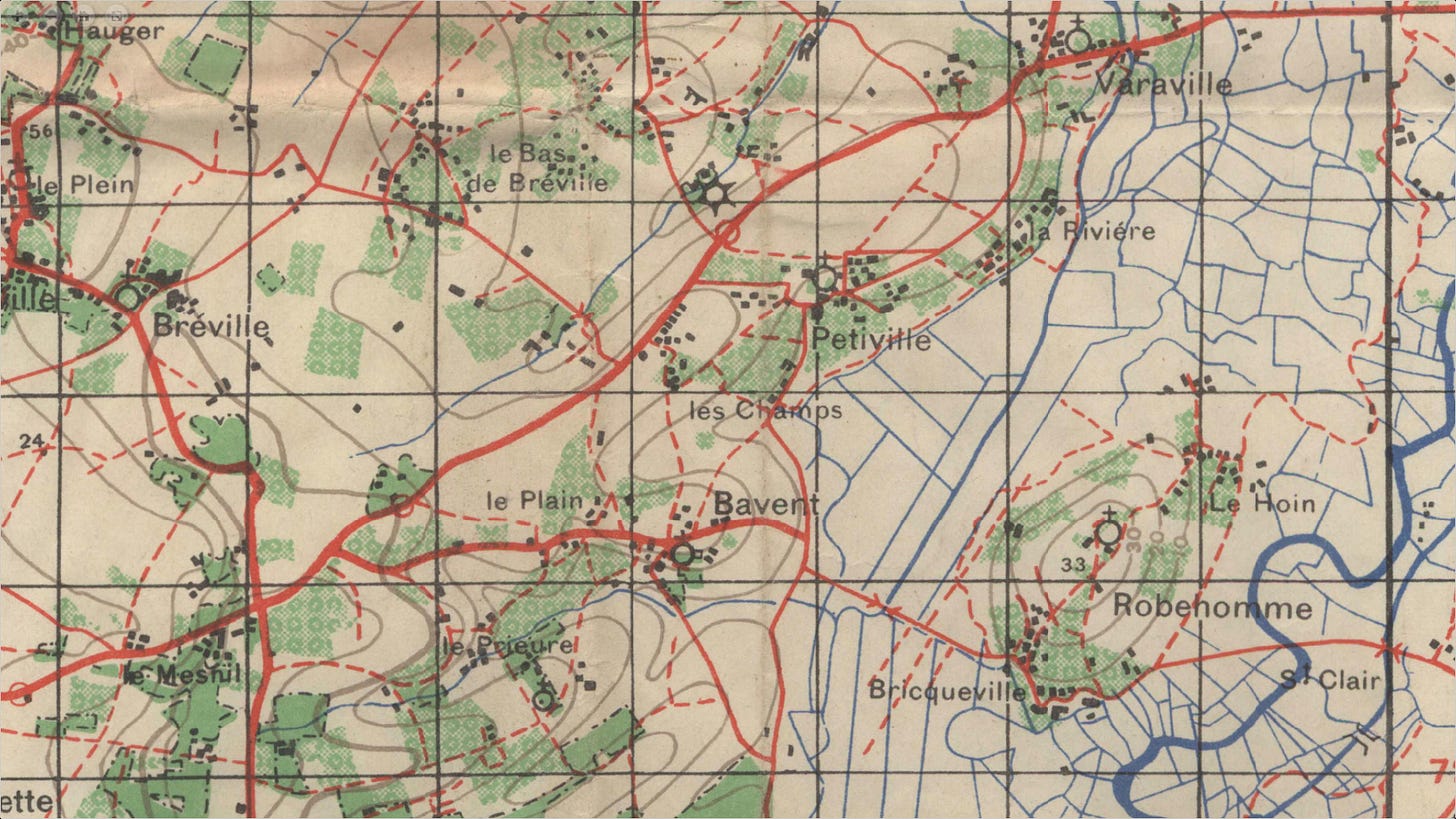

Reynolds: “When we hit flack opposition the plane bumped and things seemed to be burning outside…” the pilot, Metcalfe, had just witnessed a Stirling aircraft blow up in front of him “…outside things seemed to be burning, booming and banging… The pilot managed to evade the enemy fire, however. He levelled off and then gave us the green light. I dragged my heavy equipment to the escape door and jumped. I was pretty excited but remember clearly that a Sten gun was poked into my windpipe and almost choked me. I released my kit bag and, wham, there I was, spread all over French soil in a little open space in an orchard. We hit the ground in no time at all and I figure I was the most scared person in continental Europe…It was pitch black and kind of eerie coming down. You didn’t know whether you’d be landing on a bunch of bayonets or not…It was dark and I imagined a sniper was hidden behind every tree…I seemed to be in a field or clearing…I picked myself up, found myself unhurt and got out of my harness. Then I ducked for cover.”

Reynolds like the rest of the battalion had a scattered drop, missing the drop zone as well as losing his 16mm Victor cine camera torn from his body during the descent. Two members of Reynolds stick did not fare too well with one landing on a tree breaking his leg and arm, another was captured and shot by the Germans survived by playing dead.

Rendezvous

Reynolds managed to find other paratroopers which was made up to twenty men “Finally we assembled and set out for rendezvous. We searched one house and found only an old, very frightened Frenchwoman. Later, on after we had seen activity in a courtyard in one villa, we sneaked up ready to do battle with the Germans only to find the men in courtyard were Canadians, including the commander who had swum three rivers getting there.”

“I started walking across the fields toward the rendezvous. There I saw Jeff Nicklin of Winnipeg [Winnipeg Blue Bomber] and our Commanding Officer [Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke]. The C.O.…quite wet…had to swim across three streams to reach the rendezvous. The other side of the zone of which we dropped was being plastered by German mortars. Our signals officer, Lieutenant Simpson…went off on a reconnaissance by himself to install a telephone exchange, which he managed to do.”

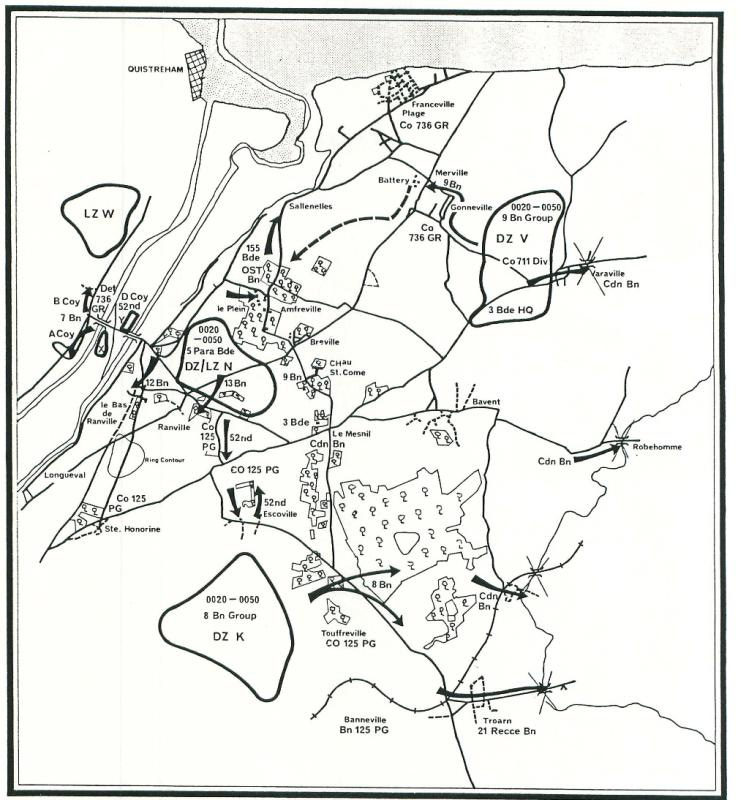

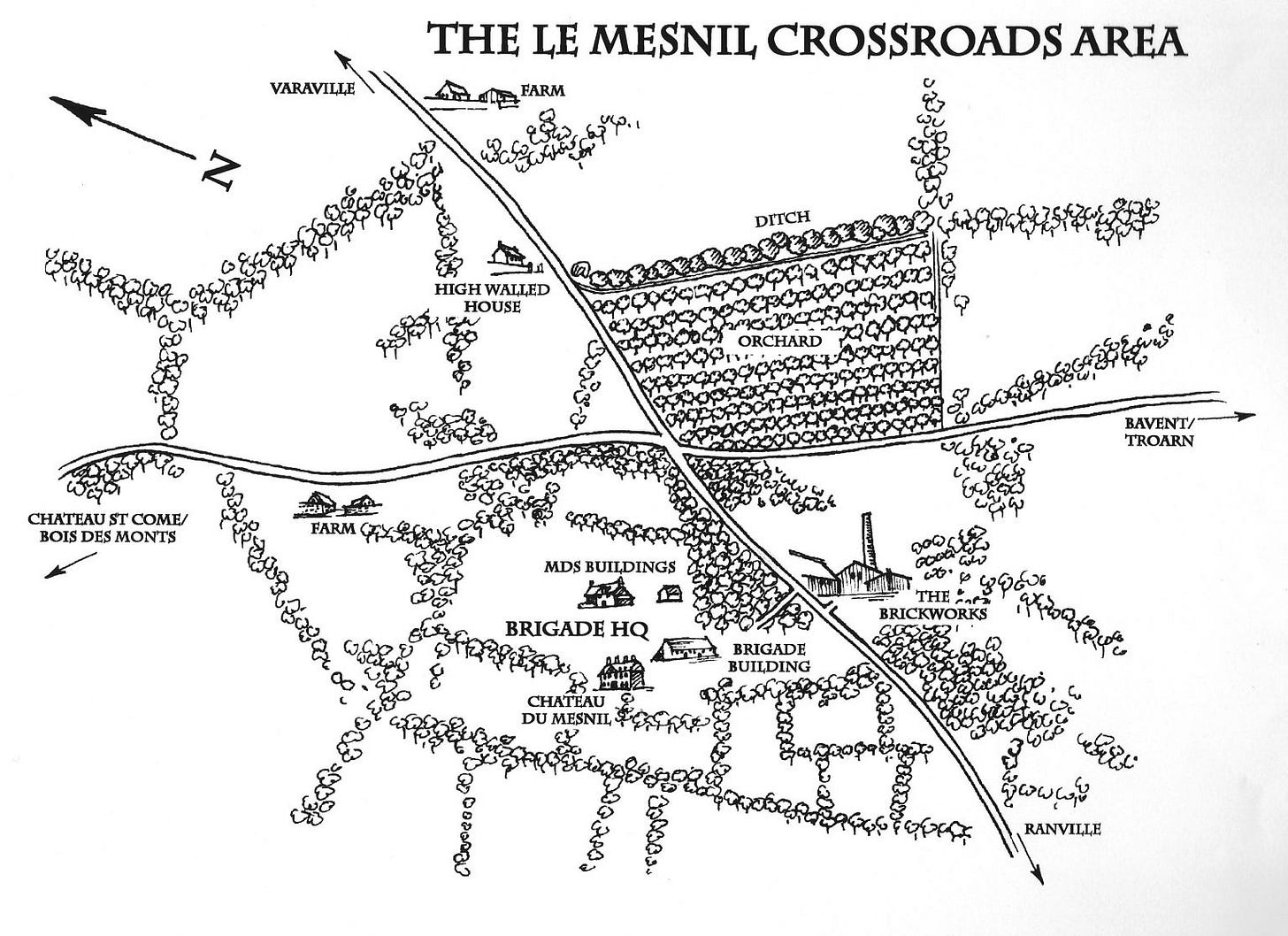

A party made up of Lieutenant Colonel Bradbrooke, Major Nicklin, a small portion of the Battalion Headquarters with medics from 224th Parachute Field Ambulance and fragments of the 3rd Parachute Brigade left the R.V. for Le Mesnil. Le Mesnil had been chosen for the H.Q. as it was nestled on the crossroads a vital junction sitting on a dominant feature and movement could be controlled in all directions.

Chateau & Glider

Reynolds went with Nicklin and five to a chateau “There was a big crater in the front lawn and one in the backyard…I tripped against a dead cow near the crater in the backyard. That was one of my, biggest scares. We found the family inside nervous but friendly. They told us the best way to reach our objective…We went up a road. There was fighting going on all around us much small arms and mortar fire. Then we saw a sight I will never forget two unarmed transport planes tugging gliders came in through solid walls of flak. They had no protection, but they came on and came through. We took our hats off to them. They sure had guts. There was a German machine gun popping off ahead. Dawn was just breaking. We crawled up a ditch to the crossroads. Our commander left the party to clear a row of houses and we moved on to a chateau in the distance. As we ran into the courtyard French people came running out to us. We were prepared to storm the place but it was swarming with Canadian paratroops.”

Chateau

…The chateau made a beautiful rendezvous because of the way we had been dropped all over the place as we tried to escape the flak. An anti-tank gun came to use by glider and it was very welcome. We moved up the road and took two prisoners who evidently loss courage and broke their guns before running into us with their arms in the air. Some of our men had a bitter engagement in a little village with snipers. We saw one paratroops dangling from a power line – dead.

Car with grenade collaborator

“We got into an orchard where the Jerries fired at us with machine guns. Later a little French car driven by a girl came clang a road. We motioned her to stop, but she speeded up, One of our men threw a grenade at the car, damaging the chassis. The girl stopped then and became almost hysterical. A young French boy we had picked up when he had identified himself as a Partisan assured us she was a collaborationist.”

Simpson returned to Reynolds having “cleaned up” the German headquarters taking 40 prisoners. They had to deal with snipers which were “thicker than grapes” the Commandos arrived around 3pm. It was at Landing Zone ‘N’ after taking his photos Reynolds then had 150 prisoners thrusted upon him “a bunch of slovenly looking ruffians…We escorted them three miles down the road to the division. There were snipers on the way...”

BEACH

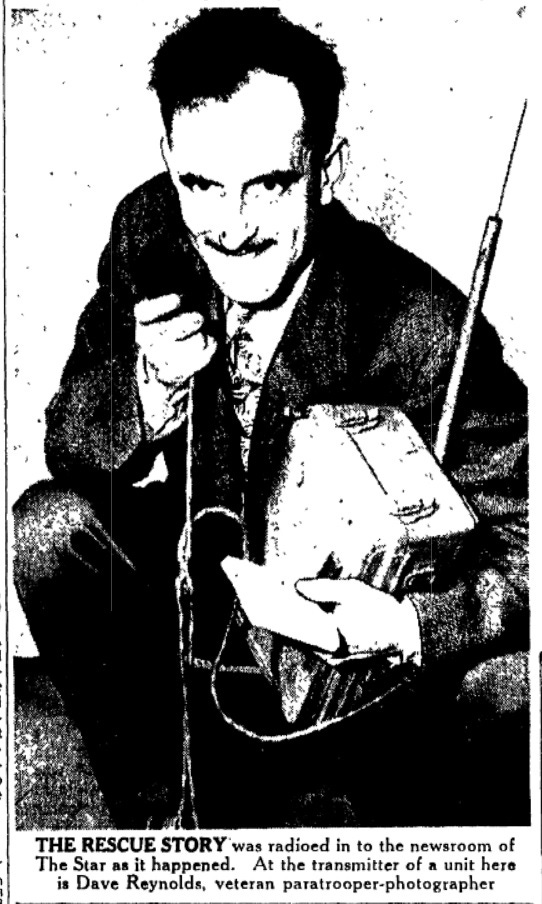

“I decided to take my pictures back. I got to the beaches, where everything was fine, well organised, well protected and running smoothly.” Reynolds last photographs are of Glider Pilots on Sword beach one holds a German K98 Mauser rifle as a souvenir. When Reynolds made it back to CAFPU in England he is said to have passed out from exhaustion, his comrades took off his clothes and bedded him down, with a few scraps of food. Reynolds just about managed to write out his dope sheets and taken 100 feet of 16mm Kodachrome and two rolls of 120 stills; and a few colour pictures. These eleven photographs are the few that we know to exist but hopefully others are yet to be uncovered.

On the Canadian Film and Photo Unit website J.E.R. McDougall noted in his field diary on 9th June 1944 “…Thursday the 8th, Sgt. Reynolds came in…I honestly hadn’t expected ever to see him again, because parachute jumping doesn’t seem the healthiest job in the world, especially on D-Day. He looked like a ghost and apparently had had quite a rough time of it. He’d shot 1—feet of 16mm Kodachrome and two rolls of 120 stills. He lost a 35mm camera and tripod. He decided to jump with only his 16mm Victor and his Rolleiflex and to send the Eyemo and tripod in by glider, where he thought they would be safer. However, the glider was hit by flak and crashed and both the camera and tripod are dead. Though the poor guy was just about out on his feet, I got him to work on his dope sheets and after much sweat, blood and tears we got the stuff off to London by DR [Dispatch rider]. Then I took him down to the mess where he told his story to the enthralled Warcos. He told the story well and the Warcos were tickled to death.”[1]

There are conflicting reports about what Reynolds manage to record and bring back to England reporter R.L. Sanburn of the Calgary Herald reported “Sgt. Reynolds brought back both still and motion pictures of Canadian paratroop activities.” though it is believed his 16mm Victor cine camera was lost on decent and the 35mm Eyemo that was placed in the glider with its tripod was also AWOL. It was also reported in McDougall’s diary Reynolds “…shot 1—feet of 16mm Kodachrome and two rolls of 120 stills.” Then is another article claiming “Although Reynolds was unable to record any footage, he joined up with a unit of British paratroops who were advancing on a group of enemy defended houses. Attesting to his combat training, he led a section into a house, clearing the building, killing three German soldiers.”

With only eleven photographs to illustrate what the 6th Airborne Division was doing on the first days of D-Day it is exciting to think there is footage or stills that exist somewhere in an archive.

I have not found very much on Reynolds after the war except that when he returned to Canada with 2,000 other servicemen in February 1945, on his return he worked at Toronto Daily Star newspaper and later with C.F.O.X. radio station and died 18th October 1987.

Reynolds final comment on the operation: “All I know is that is that it was marvellous how we were flown to our rendezvous and how, in spite of the heavy flak and some scattering we found it and got organised the way we did. Everyone sure did a grand job.”

FIRST D-DAY PHOTOS

“First invasion pix” these are eleven known photographs taken during the first few days of D-Day by Canadian army photographer Sgt. David Reynolds of No. 3 Public Relations Group. He parachuted on 6th June 1944 with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

[1] https://canadianfilmandphotounit.ca/2015/06/06/d-day-june-6th-2015-by-dale-gervais/#comments